The main object of anthropology is nameless individuals making up a group of people. When studying the past of the humanity, demographic indicators are particularly important because they can explain the ecology and culture of people who lived in different periods, the forces determining territorial expansion, regularities of change in the gene pool, and the like. A lot of information about the daily life of people in the past can be obtained by studying human remains.

The Late Paleolithic period (about 10000-8000 BC). Anthropological finds of this period have not yet been found on the territory of Lithuania. We can only guess that during the retreat of glaciers (in the 10th millennium BC), small groups of wandering hunters would follow reindeer herds coming from Central Europe. There were few of them because in the territory of the present-day Lithuania, only several thousand people at most could have subsisted on hunting and gathering.

The Mesolithic period (8000-5500 or 5300 BC). Along with the warming climate and expanding forests, the nature of hunting was changing. With the emergence of fishing, communities became more settled and the population was increasing. 5 graves of this period are known in Lithuania in Donkalnis and Spiginas cemeteries (Telšiai district). According to the data of the graves, it can be stated that the people of that time were not tall (men were about 166 cm tall; women, about 156 cm), of a stocky build, had medium-sized round heads, widish faces. Severely worn down teeth indicate that people were eating coarse food. Injuries on healed heads after possible scalping and injured wrists testify to conflicts between or within communities.

The Early Neolithic (5500-3400 BC). During this period, there is a gradual transition to farming – first, at the seaside and in western Lithuania and later, in the eastern part of Lithuania. At present, 7 graves dating from the Early Neolithic are known: these are Spiginas grave and 6 graves from Kretuonas settlement (Švenčioniai district). The available anthropological material shows that the people of that time were even shorter than in the Mesolithic (men were about 158 cm tall; women, only about 148 cm). The dimensions and the shape of skulls do not differ from those of the Mesolithic inhabitants: medium-sized rather round heads, wide and flattish faces. The shape of teeth would indicate that early Neolithic people were similar to Mesolithic people. Interestingly, even then, their teeth were damaged by caries, which can only occur only by consuming more carbohydrates, which are obtained by eating plant-based food.

The Middle Neolithic (3400-2400 BC). We do not have anthropological material from this period yet.

The Late Neolithic (2400-1500 BC). During this period, farming takes root at the seaside and in western Lithuania once and for all. In Lithuania, 4 late Neolithic graves are known, which can be attributed to the corded ware pottery culture: one grave each in Spiginas and Gyvakarai (Kupiškis district) and two graves in Plinkaigalis (Kėdainiai district). Anthropological material shows that people of the corded ware pottery culture were very different from previous inhabitants: men were about 176 cm tall, their heads were massive, elongated, their faces were flattish, noses were narrow and protruding. Due to the hard physical work, joints of people of that time quickly wore out.

At the end of the Late Neolithic, Pamariai culture was formed in western Lithuania, which took over the earlier traditions of Nemunas and Narva cultures as well as of the corded ware pottery culture. We have anthropological data of this period from 6 graves in Donkalnis burial grounds. People of the Late Neolithic were of smaller build than the ones of the corded ware pottery culture and similar to those who lived 2000 years ago: short (men – about 168 cm, women – about 150 cm), stocky (weight was about 74 and 47 kg, respectively), with moderately large round heads, medium-sized faces. Meat became more important in nutrition. Changes in bones show periodic starvation or illnesses, which testifies that it was still difficult to obtain food resources from farming. Due to insufficient nutrition, adults suffered from the periodontal disease, caries, and injuries were common.

The immigration of people of the corded ware pottery culture did not leave a significant trace in the gene pool – the population remained essentially the same as in the Mesolithic. The biological continuity of the inhabitants of the Mesolithic and Late Neolithic is also evidenced by the continuation of burial traditions: people buried the dead in the same places for millennia (Spiginas, Donkalnis burial grounds).

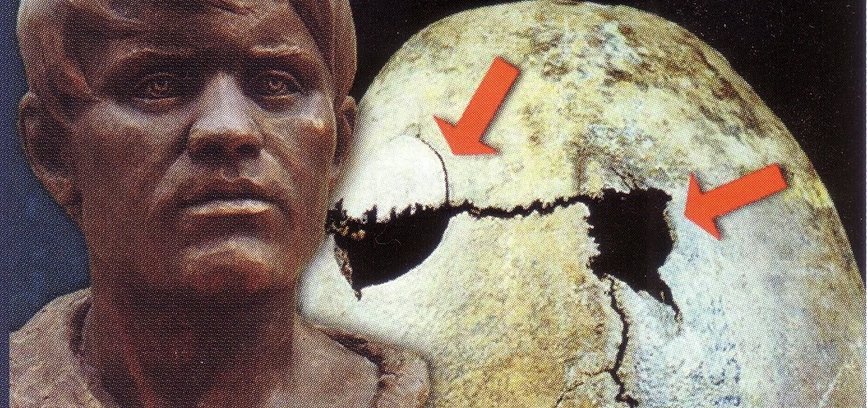

The Bronze Age (1500-500 BC). During this period, the custom of burning the dead spreads on the territory of Lithuania; therefore, anthropological material is scarce and it is often accidental in nature. One skeletal grave of an elderly man, dating back to the Bronze Age, was found in Kernavė, Pajauta valley. Finds from the end of the Late Neolithic-Bronze Age have been discovered in the peat bogs of Kirsna (Lazdijai district) and Turlojiškė (Marijampolė district). The human remains of 6 people were found here. All of them are young or middle-aged men with roundish heads, medium-sized flattish faces and small noses, the average height of men is about 168 cm. The vaults of two surviving skulls are unhealed from injuries, which is a clear trace of violence. These injuries probably reflect the increased social conflicts of that time.

The Early Iron Age (550 BC-1st century AD). Due to the spread of the custom of burning the dead, there is almost no anthropological material from this period.

The Old Iron Age (1st-5th centuries). In the first centuries after Christ, due to more efficient farming, the population on the territory of Lithuania was rapidly increasing. This is reflected in the abundance of anthropological finds. 1131 graves were examined in the largest found burial grounds of this time in Marvelė (in Kaunas city). This monument is attributed to the group of flat cemeteries of central Lithuania.

Anthropological data show that in the first period of the Old Iron Age (150-300 AD), a community of 70-85 people lived in Marvelė: on average 15 small children (up to 5 years old), about 20 older children (5-14 years old), about 25 young people (15-30 years old), 15 mature-aged persons (30-50 years old), and only 1 elderly person (over 50 years old). The average life expectancy of all births is very short – only 21,89 years. The ratio of men to women is slightly unbalanced – only 0,84; i.e., there were slightly more adult women in Marvelė at that time. Women used to give birth 4-5 times on average, and only 2-2,5 children of those born reached maturity (15 years).

The demographic indicators of the second period of the Old Iron Age (300-450 AD) were worsening significantly. A higher ratio of graves of dead young children was found – 23%; therefore, the average life expectancy of all those born is significantly lower – only 16,30 years. According to archaeologists, this reflects the community’s disintegration and burial in families. The ratio of men and women equalizes (1,04). Women give birth slightly more – on average 4,8-5,6 times, but due to increased mortality, only 2-2,3 children reach maturity. Such number of children is insufficient to replace the generation of parents – more people die than are born. At that time, a small community of only about 30 people lived in Marvelė: 6 small and 8 older children, 9 young people, 8 mature people, sometimes 1 elderly person. Demographic indicators of the Old Iron Age suggest that there was a kind of “demographic crisis” during this period: the population decreased significantly, and the mortality rate of children and young men increased.

Relatively few human remains with injuries were found in Marvelė cemetery: these are healed skull injuries and limb bone fractures. The lesions on some skulls testify to the practice of trepanations, when a hole is made in the vault of the skull without damaging the brain. Injuries clearly differ by gender: 11 males and only 4 females were found with skeletal injuries. It seems that only 5 or 6 injuries were clearly violent in nature; in later times, the number of such injuries was much higher. The violent traumas suffered by Marvelė people resemble the consequences of domestic conflicts rather than combat encounters. This shows that they lived a more peaceful life at that time. The human remains found in the ancient grave of Marvelė quite often have various joint pathologies, which indicate the differences in the lifestyle and occupations of men and women: men’s shoulder and hip joints were most heavily burdened; in women, the waist was slightly more loaded. This testifies to the former division of labour between men and women.

Lithuanian people of the Old Iron Age were of medium height (men, about 170 cm, women, about 160 cm), of a stocky build (weight was about 70 kg and 65 kg, respectively). No significant fluctuations were observed in different periods. Anthropological studies have revealed a certain regularity in the geographical diversity of people. The skulls of the people buried in Nemunas delta flat burial grounds and graves with stone circles were medium-sized, elongated, with narrow faces, while the skulls of the people found in the burial mounds of Samogitia and northern Lithuania and of people of central Lithuania, representing flat grave culture, were much more massive, elongated, with narrow faces and prominently protruding noses. More towards the east (the brushed pottery culture area) and towards the south, skeletons with particularly massive elongated heads and broad faces and skeletons with moderately massive round heads with broad faces were found.

The Middle Iron Age (5th-8th centuries). There is a particularly large amount of extant anthropological material from this period in Lithuania. The demographic situation is best reflected by Marvelė Middle Iron Age and Plinkaigalis burial grounds.

Plinkaigalis community of the Middle Iron Age consisted of about 50 people: 7 infants and children (up to 5 years old), about 12 older children (5-14 years old), about 14 young people (15-30 years old), 10 mature adults (30-50 years old), and only 1 elderly person (over 50). Women would give birth an average of 4,9-5,7 times, and of all those born, 2,3-2,6 children would reach maturity. The average life expectancy of all births is slightly higher than in previous periods – 23,93 years. These data show that the population was increasing.

The data from Middle Iron Age graves in Marvelė significantly differ from earlier periods and most likely reflect different realities of community life. Unusually few graves of children under the age of 5 (14,4%) were found here, and there were almost twice as many male graves as female. The average life expectancy of all births is slightly higher than in the Old Iron Age – 18,74 years. Women in Marvelė used to give birth an average of 4,6-5,4 times, but only 2-2,4 of all children would reach maturity. Although the demographic situation was improving, it was still worse than in Plinkaigalis community. This could have created conditions for immigration, especially of young men. In addition, injuries increased significantly during this period. They differ considerably by gender: in Plinkaigalis, injuries were found in 16 men and only 1 woman. About two-thirds of all injuries are definitely violent in nature and apparently reflect the conflicts that took place between communities. Meanwhile, the joint damages are almost indistinguishable from the ones experienced by humans of the Old Iron Age and confirm the sexual division of labour.

The body dimensions of Middle Iron Age humans are quite similar to those of people who lived in earlier periods. People were of medium height (men – about 170,5 cm; women – about 164,5 cm), of a stocky build (body weight was 74,6 kg and 65,5 kg, respectively). A more detailed anthropological and archaeological analysis showed that height, at least in Plinkaigalis community, depended on the person’s social status. It turned out that men buried in graves with the abundance of shrouds were taller than the average height of men – 176,3 cm tall, while in graves without shrouds, men were only 171,6 cm tall. Meanwhile, no differences were observed in women’s height. Based on these data, it can be stated that already in the Middle Iron Age, Lithuanian communities were not homogeneous. It is natural that social differences are more pronounced among men. People buried in rich graves, especially men, had more favourable living conditions as early as in their childhood, which shows that the position in the society could have been determined by origin, not only attained.

A certain change in the appearance of people is also noticeable in the Middle Iron Age, which can be explained by the possible migration of eastern Balts to the west at that time. During this period, in the areas inhabited by Selonians and Semigallians, people with particularly massive elongated heads and wide faces appeared in the eastern and western Upland Lithuania. They are associated with eastern Balts. These people push big people with elongated head and narrow faces, who previously had occupied the central territory of Lithuania, to the west, further into Samogitia, and the latter push the smaller-skulled narrow-faced people, typical of western Balts, to the very seashore.

The Late Iron Age (9th-12th centuries). During this period, the custom of burning the dead takes hold in almost all Lithuania; therefore, very little anthropological data is available. Only in northern Lithuania, in the territories inhabited by Semigallians and Selonians, the dead are buried without burning. The inhabitants of these areas were tall people (men were about 176,7 cm tall; women, about 161,3 cm) with extremely large elongated heads and wide faces.

Cremation graves are still in the early stages of examination. Their analysis enables to state that in the Late Iron Age, social differentiation continues to emerge. In the barrows of eastern Lithuania, most shrouds are found in the graves of young men and 25-35 year old men. Older men are buried with more modest shrouds or without them at all. This shows that the society of that time valued strength and the opportunity associated with it to establish one’s status in the community with a weapon.

Source of information: project of Latvia-Lithuania cross-border cooperation programme 2007-2013 “Baltic Culture Park” (Šiauliai Region Development Agency).